Ground cherries is interesting new crop to domesticate, but unfortunately domesticating in many cases is like looking for a needle in a haystack. I can sow tens of thousands of seeds to look for the most cold tolerant, but besides that the most interesting traits are only evident later in their life cycle when I don’t have as many plants. That’s why it would be good to have as many people growing as many plants and looking for interesting traits. This community might still small to easily find significant mutations, but it’s more likely than me byself. This year I had some 30-40 mature plants and I don’t think I will have more than 100 in the near future.

Traits that I find interesting are fruits size, lobes in the fruit, amount of petals (latter 2 are related to fruit size), amount of fruits in leaf nodes and possibly some growth habbits, although not sure what would be best. Fruit not falling once they are ripe would be useful as well, but that might be hard as it either is or is not. Fruit size could be improved incrimentally by several different mutations.

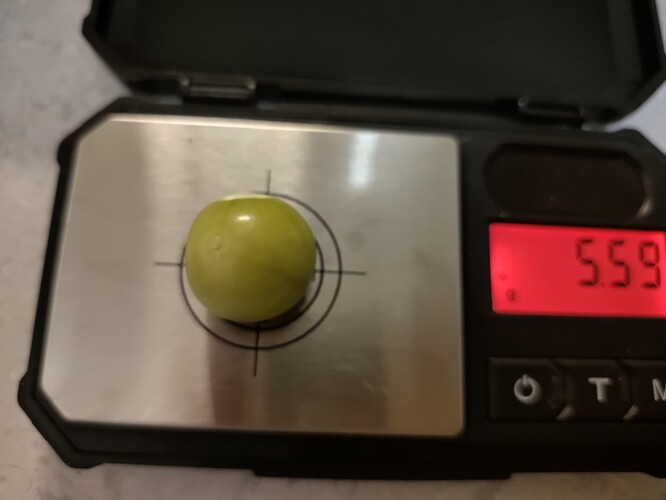

This year I thought I would really make the effort and try to select for the biggest fruits. For that I bought a precision scale (only 20€). I’m selecting for earliness and fruits size so I first saved a patch of the earliest fruits. After that I have started to scale every bigger fruit and selected the biggest. At the monent I have had cut off at 3.5g. There has been one plant that is doing clearly the biggest fruits; almost all over 4g when otherwise there haven’t been many over 4g. I don’t know if that one plant is special or if the size is relateted to the fact that it doesn’t have as much competition. I still save fruits from that plant separately. I save all over 3.5g to keep some variance and try to slowly move the limit up in the coming years.

Biggest fruit still didn’t break 5g, but fruits have gotten bigger the more ripens. I have picked them daily and some have been little underripe because they have ripened so fast over the last few days with warmer weather. I try to avoid that they fall to the ground where they are more easily accessible to rodents.

Only 2 fruits that i picked from plant that makes the biggest and 2 of the bigger fruits from all the rest. Mostly fuits aren’t even that big and 2-3.5g is more common size.

Just slightly smaller than 1€ coin.

I would also be interested in interspecific crosses beyond grisea/pubescens/pruinosa complex. I have tried cross with angulata, but only got 2 seeds that didn’t germinate using angulata as pollen donor. Not sure if embrio rescue would work and if it after that could be used to make back crosses. So I don’t think I will use effort to make those before I have some information if it’s worth the effort. There should be some other species that cross more easily, but it seems to be hard to find any information about it.

Ps. I might have little weird consept of having fun, but I find it exciting to go through fruits and weighing them with a precision scale. It’s like a little treasure hunt. I could take thousands of fruits, weight and sort them by weight. I don’t think there will be that many once I make the final harvest, but should be at least several hundred. It’s even more interesting coming years when I try to see if I can improve on the biggest.